LUCSUS recently featured the research and recent article on perspectives on loss and damage by Director Emily Boyd. This week, Stephen Woroniecki, follows up with a comment on a contribution by Dr Koko Warner, Manager of the Climate Impacts, Vulnerabilities, and Risks subprogramme, which includes the loss and damage workstream at the Secretariat of the UN Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

– This week we are glad to be able to take the conversation on loss and damage a step further with the contribution of Dr Koko Warner, says Stephen Woroniecki.

– In the following piece, she describes how the conversation around loss and damage and displacement is taking place within the UNFCCC, the principle platform for climatic issues at the global level. She then goes on to describing how different policies processes associated with human mobility are taking shape at the same time, providing a window of opportunity for the research community as well as civil society, to contribute to a safe and just international policy for decades to come.

Introduction

Terminology matters a lot in international policy about human mobility. There are different kinds of movement at play when it comes to climate change. Since 2010 when it was introduced in international climate policy, the topic of migration, displacement, and planned relocation has been framed as a climate risk management issue along a “resilience continuum”, moving away from a risk/crisis framing. The work on climate impacts, vulnerabilities, and risks puts human mobility in the context of preempting, planning for, managing and having contingency arrangements to aid society deal with climatic stressors that get in the way of sustainable development. Helping countries bolster resilience in the face of climatic risks – the ability to withstand disruptions that pose barriers to human welfare – is a central aim of climate policy.

The purpose of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is to hinder the disruptive potential of anthropogenic climate change “in order to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner” (UNFCCC Article 2).

In 2015—the same year as the Paris Agreement was concluded—the international community committed to the Sustainable Development Goals and to leave no vulnerable group behind in the quest for improving human welfare worldwide. Yet these climate stressors interfere with many of the factors that facilitate a safe, dignified, sustainable life in some areas of the world.

These stressors contribute to insecurities in livelihoods, food systems, health, social stability and others that are often considered push factors in migration, displacement, and planned relocation. Extreme events, changing weather patterns, glacial melt, coastal inundation, desertification – interact with other factors that affect how well and where people can live.The Paris agreement established a bandwidth of between 1.5 and 2 degrees C that is useful for future planning, especially loss and damage and related displacements. Loss and damage carries a gloomy, discouraging and un-redemptive weight. There is perhaps room here for new narratives about ‘falling and rising again’.

Migration, displacement, and planned relocation under the UNFCCC process

The first time human mobility was recognised in international climate policy was at COP16, when Parties to the UNFCCC adopted the Cancun Adaptation Framework, including para 14(f) on migration and displacement:

14. Invites all Parties to enhance action on adaptation under the Cancun Adaptation Framework… by undertaking, inter alia, the following: …. (f) Measures to enhance understanding, coordination and cooperation with regard to climate change induced displacement, migration and planned relocation, where appropriate, at national, regional and international levels;

The wording of this text is important, in part because it names a range of things that need to be done (measures like research, coordination, cooperation), a range of types of human mobility (displacement, migration, planned relocation), and different levels(national, regional, international). This was more than a mere mention of the issue, it is a framework for taking action. Inclusion of a sub-paragraph on migration and displacement gave options for undertaking activities to address human mobility.

Another significant milestone in climate policy happened with the 2015 conclusion of the Paris Agreement, which established a Task Force on Displacement:

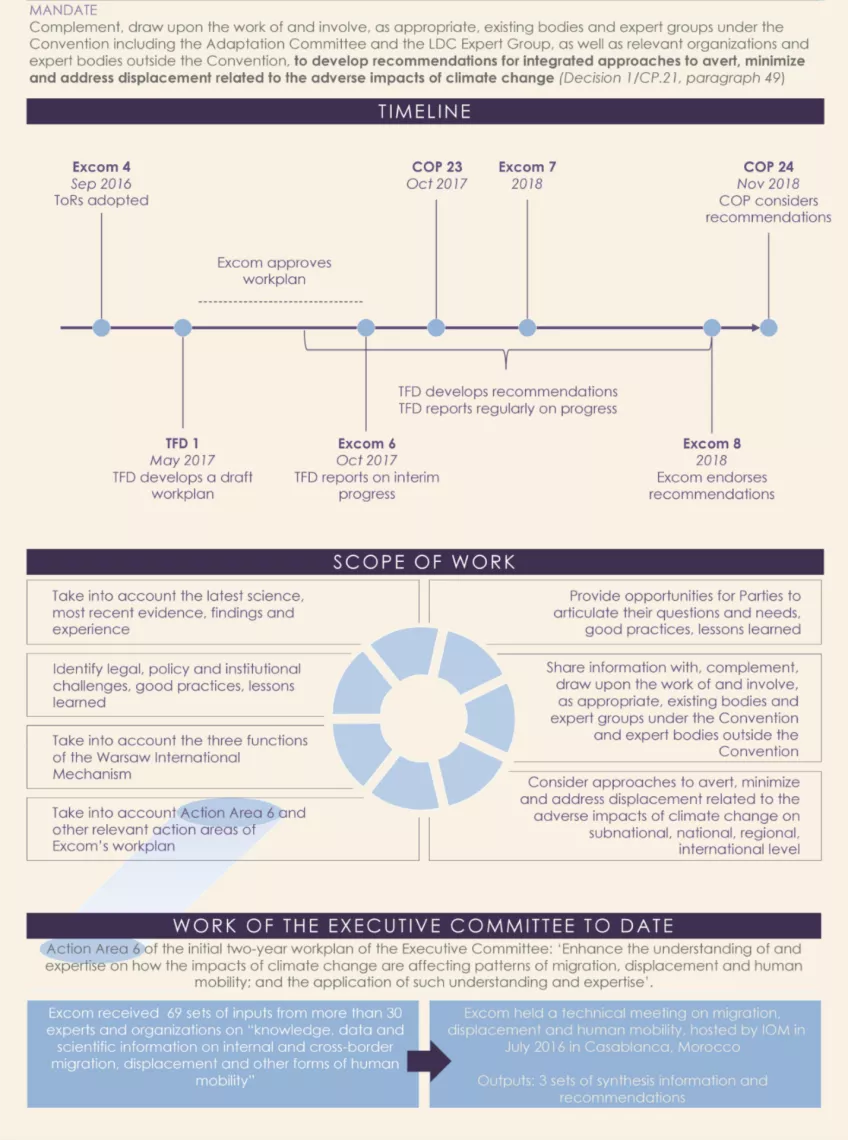

49. Also requests the Executive Committee of the Warsaw International Mechanism to establish, … a task force to complement, draw upon the work of and involve… existing bodies and expert groups under the Convention including the Adaptation Committee and the Least Developed Countries Expert Group, as well as relevant organizations and expert bodies outside the Convention, to develop recommendations for integrated approaches to avert, minimize and address displacement related to the adverse impacts of climate change:

The Task Force is embedded in the work outlined in Article 8 of the Paris Agreement, which focuses on “averting, minimizing and addressing loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change, including extreme weather events and slow onset events, and the role of sustainable development in reducing the risk of loss and damage”.

The language in paragraph 49 above shows how current climate policy work on human mobility engages relevant experts and communities of practice. This makes a difference because the mainstream perspectives and knowledge about migration and refugees combine with unique perspectives from the climate policy arena. Appointed members of the Task Force on Displacement draw from organizations that are also actively engaged in the discussions on the Global Compacts on Migration and Refugees. The inclusive approach of the Task Force on Displacement promotes a cross fertilization of ideas with the Global Compacts at a decisive time when both processes move into the critical implementation phase.

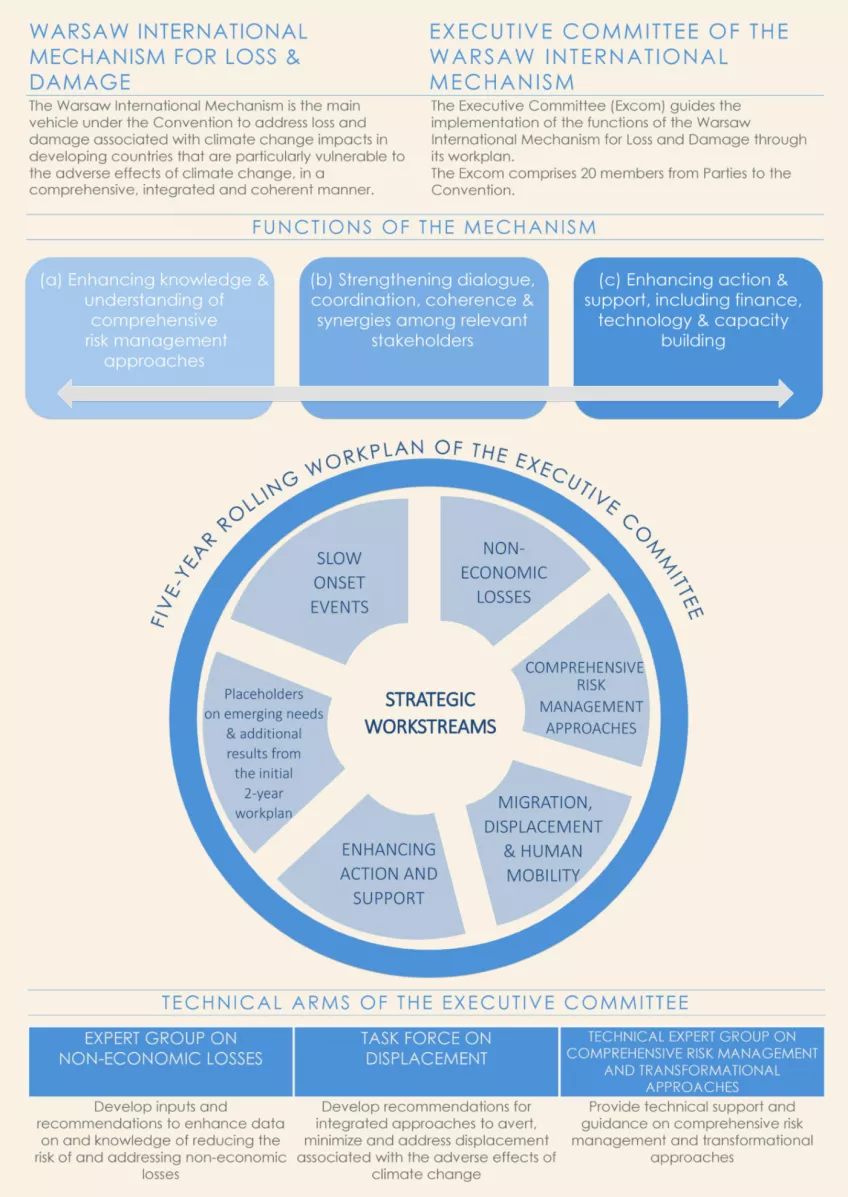

The diagrams below introduce the institution that houses the Task Force—the Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage—and its functions, strategic workstreams, and the technical arms of the Executive Committee including the Task Force on Displacement. Human mobility features both as a theme in the workplan, as well as a technical arm of the Executive Committee of the Warsaw International Mechanism.

The Task Force will develop its recommendations in the course of 2018. The task force’s work spans evidence and experience with human mobility, gathering questions and challenges facing countries and institutions, and considering approaches that avert, minimize and address displacement related to the adverse effects of climate change.

Conclusions

Building societal resilience to these climate stressors is a central aim of climate policy under the UNFCCC process. The Paris Agreement set the parameters for a climate neutral world by mid-century, which provide the international community the scope of climate impacts that could affect large scale movements of people.

Ongoing work under the UNFCCC process, such as the Warsaw International Mechanism, aims to bolster the capacity of countries to make risk-informed decisions about preemptive activities, planning, and contingency arrangements that affect where and how people live. At present, the Task Force on Displacement is developing recommendations that will be considered at COP24 in Poland at the end of 2018.

The next steps include the global community devising ways to take up the recommendations in ways that avert, minimize, plan for, and put contingency arrangements into place for human mobility in a climate-resilient, sustainable future.

The transition to a safe and dignified future means a whole different conversation and willingness to create new common ground, and that means new kinds of stories about climate and mobility; in a climate-changed world, how will we live, and where?